development: Creating a community curated collection through student empowerment. Journal of Library Outreach & Engagement, 3(2023), 119-135.

Friday, May 9, 2025

Community-Curated Collection through Student Empowerment

development: Creating a community curated collection through student empowerment. Journal of Library Outreach & Engagement, 3(2023), 119-135.

Background Essay on Collection Development, Evaluation, and Management for Public Libraries

Huynh, A. (2004). Background Essay on Collection Development, Evaluation, and Management for Public Libraries. Current Studies in Librarianship, 28(1/2), 19–37.

Timothy Wager

Summary:

The author surveys the history of the philosophy of collection development from the early 20th century to the beginning of the 21st, focusing on public libraries and examining seven influential monographs. Huynh points to the general shift over this 100 year period away from selecting “great” literature in an effort to educate the public to acquiring books that circulate more frequently, meeting public demand. Furthermore, she outlines the transition of library acquisition philosophy from book selection in the early 20th century (selection policies and processes derived from community assessment), through collection development in the 1960s (which includes activities like budget management, community outreach, and collection analysis), and eventually from the 1980s onward, broadening to collection management (which includes acquisition, weeding, storage, preservation, marketing, and organization). The article points out that the librarian’s role, then, has evolved from selector and keeper of books to a manager of items, information, and systems, including electronic resources.

Huynh provides a brief history of public libraries in the US, pointing out that the Boston Public Library (the very first major public library in this country) was founded with the goal of providing an education for those people who could not afford it. Most libraries that were founded in its wake held the same principle as central to their mission, and book selection was consequently focused on choosing “great” books that would provide some form of educational uplift. As a secondary education became more readily available to the American populace, several influential mid-20th century librarians argued that a library’s purpose was not to educate, but to meet the demand of its patrons, making itself useful to the public at large. Later, by the 1970s, the philosophy of the “great” books was rejected as elitist, and so a librarian’s service to the public shifted to meeting its demands.

Huynh broadly and briefly summarizes how libraries have traditionally worked up their collection development policies, beginning with a needs assessment of patrons; continuing with identifying resources and constraints; and developing written policies based on these factors and the driving philosophy behind the library (educating the public with “quality” resources or responding to public demand, or perhaps a combination of the two). Early collection development policies, based on selecting the best books, were time consuming and demanded that librarians know literature broadly and deeply. As policies shifted to meet public demand (and more and more books and materials were published), librarians began to rely on market-driven data provided to them by contracted services or gathered from periodicals and newspapers to make buying decisions. Earlier librarians needed to know books to fulfill selection policies; current librarians need to know their readers.

The author then runs through each of the seven monographs’ stance on acquisition, de-selection, and evaluation, illustrating how the purported purpose of a library has always been a strong guiding principle in decision making about collection development. She concludes by noting just how much competition there is in the information marketplace, and that libraries need to define and advocate for their relevance, and collection development has a large role to play in accomplishing this goal.

Evaluation/Review:

This is an excellent summary article, written when the author was a graduate student in a collection development course. While it may seem basic to veteran librarians, as a primer for students or new librarians, it provides a valuable introduction to the history of and philosophies behind collection development. To a degree, Huynh drives the central point — the shift from education to entertainment as the main purpose of library collections — into the ground. This point is repeated multiple times, but it is, while perhaps simplistic, interesting and applicable. Overall, she does a very good job of summarizing the publications she covers, each of which she treats as representative of an era in library history. Whether these monographs actually are representative I leave to others more versed in collection development history. While it is isn’t really an entertaining read, it is informative and well structured. This would make a great article to assign in a collection development or collection management course.

Sunday, March 30, 2025

Policies for Library Inclusion of Self-Published Works

Burns, C. (2016, February 4). Policies for library inclusion of self-published works. Public Libraries Online. https://publiclibrariesonline.org/2016/02/policies-for-library-inclusion-of-self-published-works/

Whipple, Karen

Spring 2025

Summary:

This short article poses the question of whether self-published works should be accessible through libraries. The article discussed how these works can easily fit into a library's collection with a few caveats. Specifically, it may be necessary to modify the collection development policy to focus on self-published works, and an agreement must be established with the self-publishing companies. As always, libraries need to consider the value of the book and the space they have available for their collection. Ultimately, the article argues for including self-published works but recognizes the library must be willing to create a firm policy and procedures for these works.

Evaluation:

This brief article was written almost ten years ago, but it has become even more relevant today. Self-publishing is incredibly easy nowadays with the help of self-publishing opportunities like Kindle Unlimited Direct Publishing (KDP), which allows individuals to electronically publish their works and even receive payment when users access and read their books. Many of these books are available in print, eBook, and eAudiobook formats.

"Indie" authors are no longer the amateurs they were once considered to be. Some indie authors have built successful careers through this nontraditional form of writing, achieving notable success in both income and readership. These self-published works are reviewed by readers on Amazon, and Goodreads, and some have Kirkus reviews as well.

The question of whether libraries should include self-published works has been on my mind recently, so I was happy to come across this article. I would have loved to have had more detailed information, but this article was relatively brief and was more of an introduction to the idea rather than a fully fleshed-out how-to guide or review of libraries that are currently using self-published works. It is unsurprising, though, as the article was published in 2016; I imagine the idea was still in its infancy. Still, it was an enjoyable, quick read to pique my curiosity.

Tuesday, November 19, 2024

A School Librarian’s Journey Through Manga Collection Development

INFO 266

Jared Miller

A School Librarian’s Journey Through Manga Collection Development - Link to Article

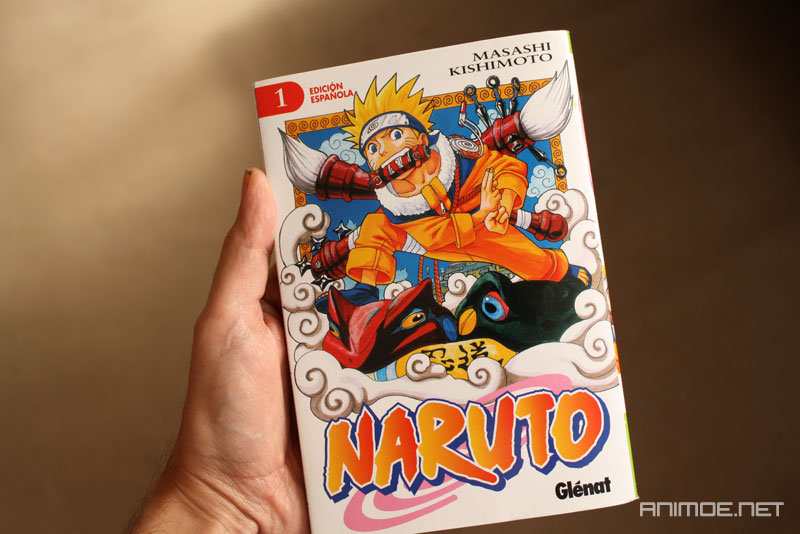

Summary: This article argues that manga does indeed belong on the shelves of school libraries and provides information and help for librarians on building a collection of Manga. Beginning by simply defining the genre or topic, the author explains that Manga is a comic originally published in Japan and is read from right to left. The author includes common misconceptions and definitions for librarians to aid in their own research and collection development. It also justifies the inclusion of Manga in a collection. Common to the work of librarians is pushback from particular parties, and having a clear rationale for why Manga is included in the collection is crucial. Manga is generally marketed toward younger readers, but has a vast following over all ages.

Evaluation: This article is a valuable resource for high school librarians interested in building a manga collection. In regards to collection development, the article provides a list of recommended manga titles specifically for high school students, categorized by genre. This makes it an extremely useful source for getting started in building a manga library. In case there is any pushback with spending money to include manga, it offers arguments for the educational value of manga, which can be helpful when advocating for budget allocation for a manga collection. This includes building visual literacy skills analysis of literary devices such as plot, theme, symbolism, foreshadowing, conflict, and character development, as well as aiding in communication skills. All of which English teachers are generally desperate to do in their classrooms. The article also suggests ideas for creating manga-themed events and clubs, promoting engagement with the library. Looking at the current make-up of my own students, I think that a club like this would dramatically increase readership at my school. Overall, this article is a valuable resource for high school librarians who want to provide their students with access to engaging and educational materials like manga.

|

| Naruto Manga - Phossil - https://www.flickr.com/photos/phossil/4811921029 |

Rudes, J. (2022). A SCHOOL LIBRARIAN'S JOURNEY THROUGH MANGA COLLECTION DEVELOPMENT. Knowledge Quest, 50(4), 36+. https://link-gale- com.libaccess.sjlibrary.org/apps/doc/A697577819/AONE?u=csusj&sid=bookmark- AONE&xid=bb6497df

Wednesday, April 21, 2021

What to Think About When Managing a Collection

Kami Whitlock

Preschel Kalan, A. (2014). The practical librarian's guide

to collection development. Retrieved from

https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/2014/05/20/the-practical-librarians-guide-to-collection-development/

Preschel shares her

thought process while weeding and purchasing books. She first talks about the

importance of knowing the library’s user population. She then shares her thought

process while weeding. She suggests establishing priorities, checking

statistics, examining the physical condition of books, and keeping guides

current. She also shares tips for materials on different subjects. One take

away from the article is to think of this process as ongoing. She is weeding

and purchasing books as much as she can throughout the whole year. This gives

her a chance to add additional copies of books that are in high demand and

adapt frequently to users needs. To be successful in this, she must be very

aware of her budget.

This article is meaningful for

librarians who are new to collection development. Although the information in

this article is brief, the points she suggests to think about are meaningful

and useful. She gives practical

examples and explainations of what to look for while making weeding and purchasing decisions.

Wednesday, December 4, 2019

What's New in Collection Development

I thought this piece was very clear and concise. It reads as a reminder to school librarians that they should be curating a collection that caters to its community. And that the library collection should be shaped to improve our learning communities.

Friday, November 23, 2018

Collaborative Collection Development for Specialized Collections

DOI: 10.1080/1941126X.2013.847690

Summary:

This article focuses on how important it is to reach out to community members in order to bring their own works into a collection. Specifically, this article focuses on chapbooks from poets which represent a difficult collection to work with for librarians because there is a constant tug between what is wanted and the quality. The idea is that by encouraging community members to voluntarily deposit their works into the library so patrons can get what they want and the collection can remain relevant to today's users.

Evaluation:

I rather enjoyed this article a lot because I think it is very important to include community members when selecting content for a collection. I noticed that with my library as well as other public libraries that there is a huge focus on the user initiating the process for collection development. Some libraries do have internal lists that they pull from, but they predominantly focus on the patrons for their development which does not always work. But, by utilizing a information community and creating a space for collaboration, Carr is demonstrating that development can occur at a local level for the collection that is still relevant and what is desired. I would have liked to have seen a broader study, but based on the scope it would have been problematic to focus on a larger collection.

Monday, May 14, 2018

Collection Programs in Schools

Bishop, Kay. The Collection Program in Schools: Concepts and Practices. 5th ed. Santa Barbara,

Summary: This Library and Information Science Textbook analyzes the definition of a collection in the 21st Century. It discusses the changing definition of a school library’s collection. This book defines a school media center’s collection as a “group of information sources, print, non print, and electronic” (2007, Bishop, p.1). It includes books, magazines, ebooks, databases, and materials available through interlibrary loan. In addition, this textbook discusses the importance of becoming knowledgeable about the existing library collection and becoming familiar with the school, the community, the school curriculum and the needs of the user. This reminds me of the needs assessment I conducted while analyzing the library I work at, The Winters Community Library. This book also offers general selection criteria for developing a school library collection including appropriateness of content, scope, high-interest, and support materials for instruction. This text also touches upon fiscal issues relating to the collection and looks at the budget process. The author suggests grant writing, alternative funding, and fundraising. Lastly this book looked at the process of weeding and offered reasons for weeding decisions including poor condition, poor circulation record, biased or stereotypical portrayals, inappropriate reading levels, and outdated information. Evaluation: I thoroughly enjoyed reading this book. It was published in 2007 so it is a modern, relevant book for school librarians and school media specialists. Topics for collection programs in schools are well organized into 17 Chapters for 17 different topics. Many of the ideas presented by the author, Kay Bishop, have been discussed in INFO 266 so it connected well with my current studies. For example, I have been analyzing my school’s collection for Presentation 4 and after reading the chapter on weeding, I have added new reasons to weed our series collection. Some of our books in our series collection are outdated and have low circulation such as Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew. It is hard to get rid of them because I have so many fond memories of reading them as a child, but this book re-emphasized the importance of creating and maintaining an “attractive collection” and some of these books are in poor physical condition.

Wednesday, May 2, 2018

Selecting While White: Breaking Out of the Vendor Box

Couillard-Smith, Chelsea. (2017, October 3). Selecting While White: Breaking Out of the Vendor Box. Retrieved from http://readingwhilewhite.blogspot.com/2017/10/selecting-while-white-breaking-out-of.html

Reading While White is a blog about diversity and inclusion in children's and YA literature. This post is emblematic of the site, since it is by a white librarian who wants to ensure that her collection is as racially inclusive as possible. As she addresses, there is not a lot of diversity in the traditional publishing world. Her suggestions are to advocate for diverse books, ask more of your vendors, and consider purchasing from small presses, independent authors, and local booksellers. Even amazon can be a source for great self-published authors that are not carried by major vendors.

I think this is a really important topic to cover. It is well-known that major publishers don't have enough diversity, but I think many people wouldn't consider going down these routes to get better representation in their collection. Independent authors and small presses are not going to be carried by large vendors, but they can be a valuable addition to a collection, and I think librarians should look into these options whenever they can.

Thursday, October 20, 2016

Budgets Are Limited, Student Interests Are Not

Ultimately, this article is about how to get more bang for your buck and Jennifer Henry’s comment (titled “Cooperation & Innovation”) has some great points about connection development that might help those of us on a tight budget not feel so constricted by that forced choice.